When we think of trauma, we often imagine an assault from the outside. But when someone is diagnosed with a serious illness such as cancer, the attacker is on the inside. People often report feeling betrayed by their own bodies.

That sentiment is common to students in Bobbie-Raechelle Ross’s Yoga Nidra class at InspireHealth in Victoria and Vancouver. Attendees come to the centre for physical and emotional support with cancer care beyond medical treatments.

“They don’t feel safe because their body is too unpredictable. Instead of focusing on their capabilities, their view of their body becomes negative,” says Ross, a yoga teacher with 500 hours of training.

This sense of being betrayed by one’s own body is also common to people in recovery from addictions, or who have experienced abuse, says Ross. She witnessed this scenario repeatedly when teaching yoga at a mental health facility and alternative high school in Winnipeg before moving to the West Coast. Hearing positive feedback about the overall effects of yoga on her students inspired her to study the phenomenon more deeply. She embarked on a diploma in yoga therapy (almost complete), and is also working towards qualifying as a registered professional counsellor.

People with cancer or other serious illnesses may numb out, dissociate, or become hyper-vigilant – all symptoms of trauma held in the body. Like abuse or assault, a serious illness threatens personal safety, and may even attack self-perception.

Suddenly, a person becomes a patient, and the illness is in charge. There may be confusing medical tests, long periods of waiting for results, and uncomfortable or painful treatments. A person may feel dependent on doctors for access to information and specialists. Choice and personal agency are compromised.

When our interoception skills are still growing, we can spend too much time cognitively getting wrapped up in the stories.

Because symptoms in cancer patients are similar to those of other trauma survivors, Ross uses trauma-informed techniques when she teaches. For instance, she talks almost continuously throughout the class.

“Silence and stillness can be difficult for people who have experienced significant trauma,” explains Ross, “because they can get caught up in the chatter of the mind.”

To avoid this internal chatter, Ross encourages students to develop interoception – the ability to perceive sensations in your body, including hunger or thirst, muscle tension, butterflies in the stomach, or excitement. Interoception skills are strongly correlated with resilience. In other words, people who are better at paying attention to their bodies are better at bouncing back from adversity.

Where regular yoga classes may begin with a silent meditation, Ross opens with a guided grounding exercise, inviting students to notice their bodies’ contact points with the floor or chair.

During the asana portion of the class, Ross invites her students to ask themselves, “Am I in my body right now? Where am I? What am I noticing in my body right now?”

“When our interoception skills are still growing, we can spend too much time cognitively getting wrapped up in the stories [related to each sensation]. My goal is to provide a somatic experience where students can feel safe to observe their own body, the sensations, or lack of.”

She had no choice in the scan; it had to be done. But she could choose to tap into this tool and come out less overstimulated.

Ross says it can take a few classes for students to warm up to the practice, but the difference is noticeable.

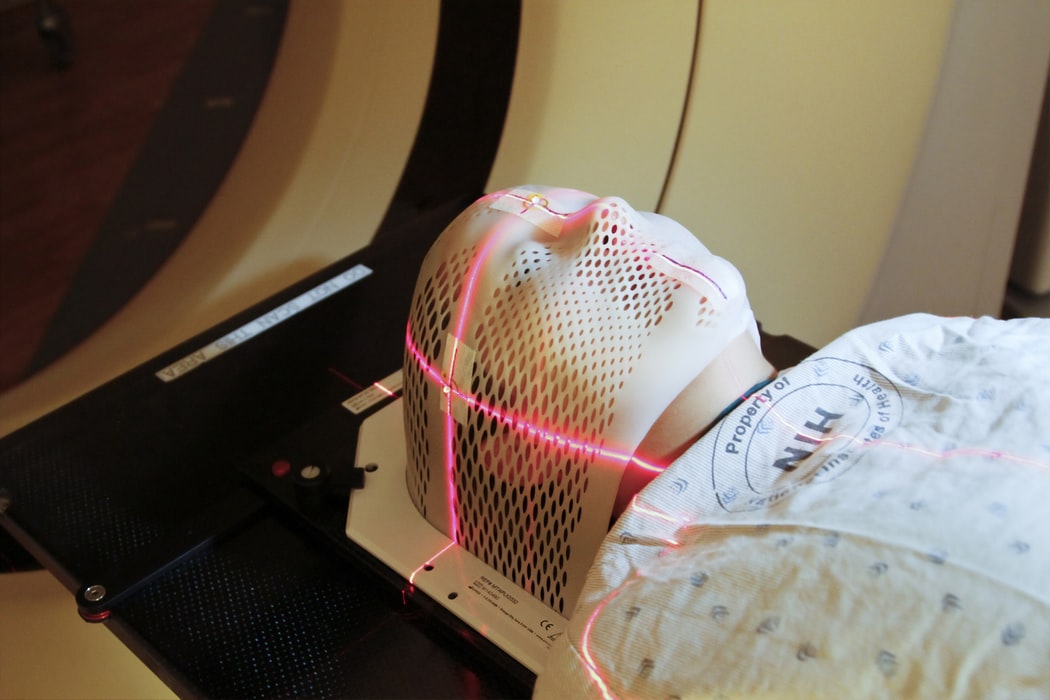

One woman was particularly frightened of CT scans, partly because of the lengthy time she had to spend inside the noisy machine. After taking Ross’s Yoga Nidra class for a month, she had a different experience.

As the scan began, the woman noticed signs of her body becoming hyper-aroused: her heart was racing and she felt sweaty. But then something new happened – she remembered Ross’s voice leading her through an exercise called Rotation of Consciousness. “Right big toe, second toe, third toe….”

“She was able to self-regulate using this coping mechanism,” says Ross. “She had no choice in the scan; it had to be done. But she could choose to tap into this tool and come out less overstimulated.”

Ross has dozens of anecdotes like this, where students share how a sensation-focused yoga class has raised their confidence.

“Having this reminder that you have a body and all that it’s capable of can be a really empowering experience moving through trauma,” says Ross. “Instead of focusing on all the negative, focus on awareness of what your body can do for you.”

In coming weeks, Ross will be taking her awareness to Turning Point Recovery Society. There, the soon-to-be Yoga Therapist will help to launch a yoga program for people building new relationships with themselves after quitting a relationship with substances. As she did with the patients at InspireHealth, Ross will be gifting her new students a safe space for connecting with their bodies.

Find Bobbie-Raechelle Ross at Breath + Reach Wellness.

For more in our series about trauma-informed yoga:

https://www.yogaoutreach.com/why-use-invitational-language-in-trauma-informed-yoga

https://www.yogaoutreach.com/why-hands-on-assists-arent-right-for-trauma-informed-yoga

Trauma-informed yoga training for teachers and health professionals:

Yoga Outreach Core Training™ – 18 hours

Yoga Outreach Certification™program: a 200 hour immersion